Putting solar on the chopping block may damage the industry

badly at a time when it just needs that last push to become independent.

Energy experts

believe a rumoured government plan to cut subsidies to solar could cripple the

burgeoning industry just before it is able to stand on its own.

Late last week the government issued ambiguous

warnings that the solar industry’s days of living off top-ups from

bill-payers were numbered. A cabinet source revealed to the BBC that

the government view had hardened further towards green subsidies and a “big

reset” was coming.

After onshore wind (currently the cheapest renewable energy

in the country) had

its subsidies cut last month, solar looks set to be next on the chopping

block. Solar insiders believe the feed-in tariff (FiT), levied from household

bills and given to those who buy rooftop panels for their homes, will be

severely restricted or abolished.

Billpayer support for renewable energy has long been a

political bugbear of the Tories. In 2013, Prime minister David Cameron called

environmental policies that

increased household bills “green crap”.

Last week, a source at the Department for Energy and Climate

Change (Decc) told

the Telegraph: “[Energy secretary Amber Rudd] is determined to get a grip

of these out-of-control subsidies and make sure that hardworking billpayers are

getting a fair deal.” Decc did not respond to a request to clarify or confirm

the comments.

Subsidies are not limited to renewable energy. Globally, the

International Monetary Fund estimates that fossil fuels benefits from direct

and indirect subsidies amounting to £3.4tn a year.

The actual amount subsidies for renewable energy is often

wildly overestimated by people paying the bills. A

study in March showed people on average estimate that £259 of a

typical duel-fuel bill goes in subsidies for wind energy. The correct figure is

£18.

Recent

research by the Policy Exchange thinktank found the contribution of

FiTs and the renewable obligation (RO) amounted to £10 and £38 respectively.

Jim Watson, the director of the UK Energy Research Centre said the contribution

of solar to the RO was “relatively small” whereas the industry benefits from

the vast majority of FiTs.

Watson estimated that, in total, solar subsidies cost

billpayers £10 per year (0.7% of the average annual electricity and gas bill of

£1,338 per year). Energy efficiency measures, targeted towards low-income

housing, cost roughly five times more.

He said if this money were to disappear completely the

government risked the industry “dropping off a cliff”.

“Were subsidies to simply stop I think activity would

probably fall off very significantly,” he said.

The competitiveness of any source of electricity is based on

its wholesale price. Renewable subsidies allow solar, wind and other clean

technolgies to compete with carbon intensive fuels like coal and gas. The

current price of solar is roughly £80/MWhr, whereas fossil fuels sell to the grid

at £50/MWhr.

“Eventually you’d want the to stand on their own two feet

and not have subsidies,” says Watson. “ The point I’d make with solar is that

costs have been reducing very rapidly. It’s not yet at that point where it can

stand on its own two feet, but any government should expect that point to be

within about five years.

“So the question is do you withdraw support now and risk it

dropping off a cliff. Or do you maintain the support, albeit at a reducing rate

for the next few years and give it that chance to demonstrate it can be

competitive.”

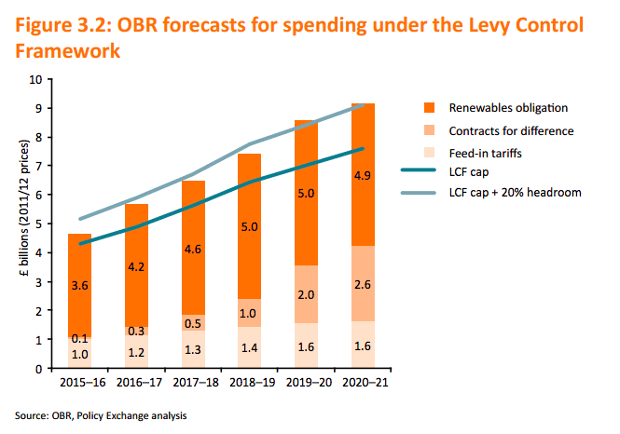

Green energy subsidies are controlled by the levy control

framework (LCF), which is a cap on the amount the government can spend from

bills for these initiatives. But the amount spent is tricky for the government

to control as it is driven by demand. This year the LCF looks set to exceed its

budgetary limit of £4.3b, although it will remain within a 20% ‘headroom’.

Policy Exchange found that without significant policy alterations, the LCF will

continue to breach the rising cap every year until it expires in 2021.

The largest contributor to overspending has been the

underestimation of the uptake of rooftop solar panels.

Britain has added more

solar capacity than any other European country since the turn of the century

and the industry set

a record this month by supplying 15% of the country’s power during a

recent heatwave. Policy Exchange found that this year the tariffs to support

home panel kits could cost £180m more than budgeted for. The thinktank

suggested restricting FiTs for small photovoltaic systems from around 13p/kWh

to 5p/kWh.

“The current feed in tariffs are far too generous, and could

withstand a substantial cut without halting deployment of solar PV,” the report

argues.

The Solar Trade Association’s (STA) Leonie Greene said their

modelling showed more than 80% of the overspend on FiTs was the legacy of the

government’s massive underestimate of solar uptake in the early days of the

LCF, which lead the government to slash FiTs by half in 2011. Notably at that

time, the industry warned the move would “kill

the UK solar industry stone dead” and yet it has not only endured but

thrived.

The industry believes it is too early for solar to go it

alone, but not by a lot. STA has produced a

plan that would see the industry off subsidies by 2020. This would

involve slowly reducing FiTs over time.

“I think it’s obvious what’s needed which is just a

sensible, structured plan over the next few years to get us off subsidy. It’s

very odd to pull up the bridge just as you’re about to cross the divide. I

think it will be very damaging, we’re not there yet,” said Greene.

“I keep hearing that we are subsidy junkies, it’s not true.

The industry wants to be off subsidies as soon as possible.”

Friends of the Earth renewable campaigner Alasdair Cameron

said he was in the process of installing solar panels on his roof.

“While costs have fallen very dramatically, there is still a

need for a feed-in tariff. Lowering the FiT to 5p/kWh as suggested by Policy

Exchange would increase the payback period of the panels from about 10 years,

to 23 years. Even 10 years is quite long, far from the huge instant returns the

government talks about,” he said.

Watson said the targeting of cheap solar was nonsensical for

a government bound by law to produce 15% of its energy from renewable sources

by 2020.

“If you are interested in meeting climate targets at lowest

overall cost, you’d be interested in promoting those technolgies which are

cheaper. There is a conflict with the overall aim of keeping cost down for

consumers,” he said.

Greene said the industry was desperate to become independent

as government policy volatility and uncertanty undermined investor confidence,

which drove costs higher.

“That’s exactly why we do want to be off subsidies. There’s

a lot of people that just cannot wait. But you have to be realistic about the

economics and about the point at which you really are at cost competitiveness

and the reality is we are not there yet. We are very close, about three

quarters of the way and we just need that last little push.”

No comments:

Post a Comment